Short intro to Quantum computation

A brief overview of problems faced by classical computers

Modern computers have come a long way and have become extremely good at solving many problems, so much so that most people might not even know that a computer is responsible behind the scenes. Recently, they have started encroaching on problems which were previously believed to be efficiently solved only by humans, like the game of go or the ability to identify hand written characters. At this stage, we can ask the question “are there problems not easily solvable by our current computers ?”. Although this question currently does not have a definite answer, there are strong reasons to believe that there are problems which require so much computation power that solving them on our current computers is practically impossible.

The main idea behind these types of problems is that they scale exponentially with the size of the problem, making it impractical to solve large problems of this type on our current computers. An interesting example for this type of problem is the Integer factorization or Prime decomposition, where the computational power required is roughly exponential of the number to be factored. Exploiting this difficulty lies at the heart of asymmetric key cryptography used in almost every secure communication method. There are many other relevant problems with practical applications which are often either at the border of possibility with current computers or just too slow to be implemented practically.

It is currently known that the underlying laws of the universe are quantum mechanical so an obvious question is “can we use the laws of quantum mechanics and compute on quantum states to improve computation power over our current computers which are based on classical principles ?”, the answer to this question turns out to be positive.

Brief overview of quantum mechanics

By our intuition, an object has a definite set of properties whether we look at the object or not. For instance, a spinning top has angular momentum whether we are looking at it or not, a really nice demonstration of this is a spinning gyroscope inside a briefcase. Quantum mechanics is weird because objects can have (different) properties depending on (before and after) the measurement. A nice example of this behavior is the case of intrinsic angular momentum of a subatomic particle, which exist even if the particle is point like with no moment of inertia. With certain steps, it is possible to get a quantum particle to have angular momentum in multiple orthogonal directions at the same time.

To grasp the full strangeness of the situation, the interested readers are recommended to go through Stern-Gerlach experiment and Quantum-eraser experiment

Advantages of using quantum states for computation

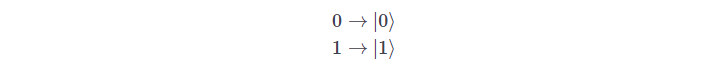

Quantum states open up a remarkable opportunity, a classical bit of our current computers can either exist in a state 0 or 1 where as a quantum bit (qbit) can exist in both the states at the same time. Let us denote the qbit states:

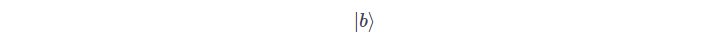

so, a quantum bit

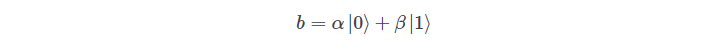

can exist in a state:

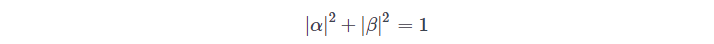

with the requirement

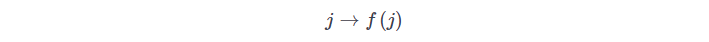

(for conservation of probability). This can be easily extended to larger integers or floating point numbers in the same way classical bits can be used to represent this. We now notice the main advantage of a quantum state, in classcical case if we have to evaluate a function:

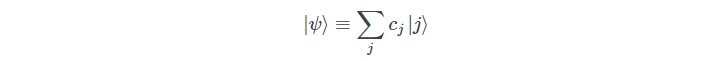

if instead we have a qunatum state:

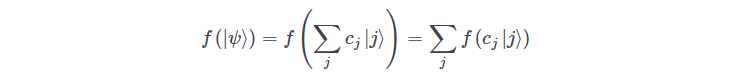

then evaluating a function would lead to:

This is one of the advantages of a quantum computer.

Problems and limitations of current quantum computers

The hardware implementing quantum computers right now are noisy and imperfect, the noise is proportional to the size (number of physical gates) of the quantum circuit. In addition to the noise, the total number of quantum bits or qbits which the computer can manipulate is, currently, very restricted compared to a classical computer. These limitations force us to think of (hybrid) algorithms which are a mix of algorithms run on a quantum and classical computers.

Semi classical algorithms for optimization on a noisy quantum computer

Motivated by the issues stated in the previous section, we try to explore if there are any advantages to use a small noisy quantum computer or variational quantum computers currently available (these are not yet practically universal), it turns out that, even with the severe size limitations, there are already applications which can get significant speed up over classical algorithms waiting to be exploited. These algorithms generally involve splitting the problem into multiple parts, some of them can be solved efficiently solved by a classical computer (problem complexity scales as a polynomial of the problem size on a classical probabilistic Turing machine. Part of the problem which cannot be effectively solved on a classical probabilistic Turing machine are delegated to a small noisy quantum computer. Since this is only a part of the full problem, it might be possible to fit this completely on a small quantum computer, also the algorithm should be robust enough to not be severely affected by the noisy nature of current quantum computers.

Many of the exponentially hard problems (for a classical computer) known right now involve discrete (combinatorics) optimization. So the main idea here is to exploit the ability of the quantum computer to explore a large number of states simultaneously, while also exploiting the robustness of the algorithm (to run on a noise quantum computer) to find a solution, which, though may not be perfect, is still an extremely good approximation of the true minima solution. We will explore some of these algorithms now.

Approximate optimization and eigen solvers

In this type of problem, the goal is optimization by approximately determining either the ground state (minimization) of a Hamiltonian matrix $H$ or its maximum expectation value. The algorithm requires us to start from a guess state (an “ansatz”) which will be improved recursively to the true optimum state, the convergence is exponential for a polynomial number of gates (this is the main “quantum advantage”, Solovay-Kitaev theorem).

Quantum annealing

The idea is similar to the classical optimization technique of simulated annealing, except instead of the temperature parameter used in the classical algorithm, the quantum tunneling property is exploited to explore many states in parallel and superposition property is exploited to reduce the size of memory required.

A brief overview of Bayesian models (gaussian process) and optimization

Let us consider the standard scenario of fitting a model

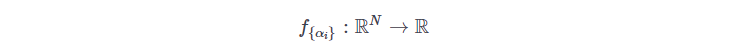

this function has the parameters

which is fit to the data points

This fit function can be then be evaluated at an unknown point $x$ to predict the outcome of the probability event at this point. But unfortunately, the function $ latex f $ cannot predict the uncertainty involved in this prediction. This deficiency is addressed in a Bayesian model which provides a probability distribution for every prediction (this is done using the Bayes theorem on conditional probability). Despite the remarkable feature of Bayesian models, they are extremely heavy to be implemented computationally so our main goal will be to deduce a hybrid quantum algorithm which might improve this computational performance.

Aravind Vijay